On the fringes of the Amazon in northeastern Brazil, many communities live in fear of attacks by invaders who slash and burn forest to make way for illegal mining, cattle and soy plantations.

This is also one of the country’s poorest regions and the low potential profits have left most communities without Internet access. According to a survey by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, Brazilians living in rural areas were far more likely to be offline than those in urban areas (53.5 versus 20.6%, respectively). In Brazil’s north, the gap is greatest, with 67.4% of rural respondents offline versus only 32.6% with Internet access.

“These are very marginalized communities that have lots of problems in struggling to survive after large landowners took their lands from them. Accessing the Internet is, for them, a matter of survival … for their physical survival, as they still have to defend themselves from attacks; for their survival as an independent cultural community; and for their economic survival. Even being able to sell their products on the Internet allows them to stay in their communities and not go to look for work in the big cities.”.

Flávio Rech Wagner, President of the Internet Society Brazil Chapter and a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

To address such challenges, in 2018, the Internet Society Brazil Chapter won a two-year $30,000 Beyond the Net Large grant from the Internet Society Foundation to build and expand community networks in three indigenous and formerly enslaved (quilombo) communities in the northeastern State of Maranhão. The project was implemented by the Institute for Research, Studies and Training (NUPEF) in partnership with the Inter-State Movement for Babassu Coconut Breakers

“The NUPEF Institute already had a very robust program for the deployment of community networks in unconnected communities in the Amazon Region, and they learned through the Internet Society Brazil Chapter about the Beyond the Net program. We were happy to ask them to prepare a proposal for submission to the program, as, in the Chapter vision, their approach was entirely compliant with ISOC’s strategy for community networks”, explained Wagner.

NUPEF builds the networks hand-in-hand with residents, installing wifi radio routers while providing training so the community can keep the network running. Internet access comes through a satellite signal that gets distributed by the routers over a larger territory. NUPEF covers all costs and maintenance for the first six months to a year.

“We organize a dialogue with the targeted communities to assess their needs, manage expectations, define priority locations for infrastructure, and figure out how to sustain the costs of the network after the end of the project.”

Oona Castro, NUPEF’s Director of Institutional Development

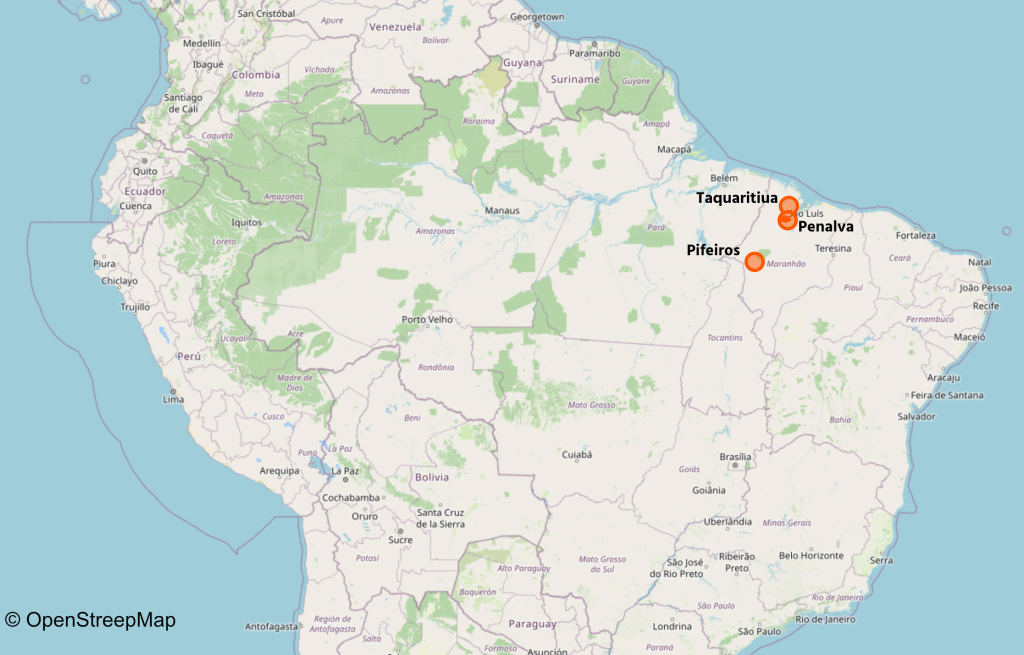

The three community networks implemented – in Taquaritiua, Pifeiros and Penalva – now provide Internet access that is collectively reaching some 500 people.

Taquaritiua

Vila Nova is a small village (population 80) in the community of Taquaritiua, located in Gamela Indigenous Territory. Before getting their network in March of 2019, residents had no Internet access.

“We live a little far apart from one another in our community but now we can use the Internet to organize meetings or discuss things without being together,” says 59-year-old resident and babassu coconut-breaker Rosa dos Santos Costa, adding that the Internet has allowed them to take orders via WhatsApp. “It would have been impossible to sell our products during this pandemic, so the Internet has really been our salvation!”

The Internet is also helping to protect the community by allowing residents to alert the Public Ministry of fires set in their territory. Costa even credits the Internet for helping the community mobilize quickly to alert neighbors and contact police after an intruder broke into a house. Costa says they expected the Internet to improve business and security, but there were unexpected pandemic-related benefits – such as allowing young people to study online, mobilizing indigenous peoples to get vaccinated, and coordinating the sewing and distribution of facemasks for the community.

Pifeiros

Pifeiros (population 100), initially received a local area network after NUPEF discovered that the local Internet service-provider they planned to use didn’t cover the area.

“We spoke to the community and they decided they wanted a local offline network anyhow, with the hope of getting connected to the Internet later,” explains Castro. “So, we configured an offline Wiki, messaging and voice over IP, and launched it in October of 2019. At first, they liked it a lot, but by early 2020, they were anxious to get full Internet access.”

NUPEF eventually found a satellite Internet provider. Then, the pandemic hit and Brazil’s National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples suspended entry to indigenous communities in March, to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

When entry restrictions were briefly lifted in October 2020, NUPEF returned to Pifeiros to establish their Internet connection, which was up and running by December.

The majority of our problems have been solved by the Internet!” hails 45-year-old resident Genival Ferreira Brito. “Before, we used to spend a whole day trying to sell our oil. Now, all we need is one call or a message … and we have been able to know and comply with restrictions.”

NUPEF also trains the community to produce local cultural and educational content that can be accessed locally, to reduce bandwidth consumption. They cover photography, audio and video recording and editing, as well as addressing online privacy and security issues.

Penalva

The Penalva quilombo (population 1,000) actually got its community network under a 2017 NUPEF project. The 2018–2020 grant enabled it to expand by four nodes, doubling its reach, speed, and data cap. The community network now reaches twice as many users – at least 300 people.

“It is a way to protect our leaders from threats. With the Internet, we can report crimes anytime,”

Geovania Machado Aires, an educator, project assistant and administrator of the Penalva community network.

According to some reports, it has also saved residents time and money by allowing them to file taxes, apply for farm or business subsidies, or submit employment paperwork online. Before, they spent an entire day travelling to the city of Pinheiro – by motorcycle, boat or horseback – where they paid $180–300 reais per document. Now, people from 50 small communities come to Penalva instead, to file them online, for free.

Internet access has also helped with cultural preservation, says Aires, praising the content production workshops. They even organized a video contest for young people to showcase their language, culture and creativity.

“It was a fantastic experience; a moment of learning,” says Aires. “Now our goal is to advance with more equipment and connections so that other communities can gain access.”